Hypercritical

Aperture ascendant

Aperture is off to a shaky start—to say the least. Apple’s new application for professional photographers has gotten, at best, mixed reviews. At worst, it’s been panned outright. Here at Ars, Dave Girard gave it a rating of 4. That’s out of 10, folks, not 5. Ouch.

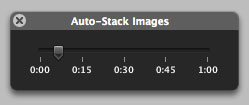

My brief personal experience with Aperture mostly confirmed the grim assessments of others. I don’t know enough about RAW processing to say much about that aspect, but performance is something that anyone with an attention span can measure. Interface lag is everywhere in Aperture, with beachballs lurking in unexpected places. To give just one example, consider the “auto-stack” feature, which groups photos based on the time they were taken. The palette that controls this feature has a slider that adjusts the maximum interval between shots. You can see a demonstration of the auto-stack feature about 30 seconds into the Compare and Select Tools video on Apple’s web site. (The palette itself is shown below.)

In the video, the response to changes in the slider’s position seems almost instant. But when I tried Aperture 1.0 on a dual 2GHz G5 with 2.5GB RAM, I got a beachball for up to two minutes if I tried to move the slider at all. This was with a collection of fewer than 200 photos.

Aperture 1.0.1 was released shortly after 1.0, and it claimed to fix the auto-stack performance problems. I had a chance to try it on a quad-core G5 with 4GB of RAM at my local Apple store. This time, the photo collection had fewer than 50 images. There were no beachballs, but it still took several seconds to react to each change in slider position. If this is the best Aperture can do on top-of-the-line hardware with only a handful of images, prospects are not good for “normal” machines with thousands of images.

(Incidentally, this is also another case of the now-classic “real-time control, non-real-time response” syndrome in Apple software. But that’s a topic for another post entirely…)

Performance was just the tip of the iceberg. In my brief experiences with Aperture, I saw drawing errors (thumbnails sheared in half, artifacts from previous selections), mysterious behavior (unexplained duplicates of photos imported from iPhoto), and plenty of good old-fashioned crashes. Again, this is with very small collections of images. So, like I said: grim.

Now let me tell you my view on Aperture’s future. I predict that Aperture will go on to become an extremely successful product, perhaps even the dominant application for professional photographers in the coming years. No, this is not just the Kool-Aid talking. I’d be a lot more pessimistic about Aperture’s prospects if we hadn’t just seen the very same scenario play out over the past few years with Final Cut Pro.

Final Cut Pro was introduced into an even more competitive market than Aperture’s, and had arguably more significant technical flaws in its early releases. (Most notably, it was saddled with a DV/NTSC codec that had serious artifacting issues—issues that remained until after Final Cut Pro version 1.2). Despite the promise of its elegant UI and the unrealized potential of the underlying technology, Final Cut Pro was a deeply flawed product out of the gate. Even professionals who wanted to like it found that they couldn’t use it for serious work until some of the big issues were resolved. Starting to sound familiar?

This comparison has been made by others, but I’ve rarely seen it emphasized to the degree I think it deserves. Mind you, it doesn’t change the quality of Aperture 1.0 one whit. But it does speak in deafening tones about the future of the product—something many reviews can’t help but predict doom for based on the dire 1.0 release.

I find the Final Cut Pro connection so blindingly obvious, and so important, that I’m surprised it hasn’t dominated all discussion of Aperture. Aperture is Final Cut Pro all over again, only with an even better start this time. Aside from a few technical innovations, Final Cut Pro was essentially a “me too” product in a field crowded with well-established applications that did the same thing. Aperture, on the other hand, has no direct peers. Several aspects of Aperture compete with one or more specialized applications, but there is no other “one-stop shop” for professional RAW image organization, editing, and publishing.

Of course, this is only an advantage if you think Apple’s approach with Aperture has merit—and, to a lesser extent, if you think Aperture’s design successfully realizes this vision. I do, on both counts. Where Aperture falls down is in the most fixable of areas: execution. That’ll come with time, as it did in Final Cut Pro. It will take longer for competitors to match the feature set and overall design of Aperture than it will for Aperture to fix enough bugs and performance issues to finally become usable.

And, like it or not, don’t forget that Apple has the unique position of also making the OS and the hardware, which gives it a significant advantage when it comes to building demanding, high-performance applications like Final Cut Pro and Aperture. Arguably, technologies like Core Video and Core Image exist because of the needs of applications like Motion and Aperture, not the other way around. In the face of such competition, even the mighty Adobe must be wary.

In short, I’m bullish on Aperture. Consider all of your feelings about Final Cut Pro 5 today. I predict Aperture will have a similar reputation when it hits version 5. In the meantime, there will be pain and missteps and many more mixed-to-negative reviews. But I believe Apple will stay the course, and mold Aperture into the extraordinary application that version 1.0 only hints at.

This article originally appeared at Ars Technica. It is reproduced here with permission.