Hypercritical

Apple Turnaround

I spend a lot of time thinking about what Apple should be doing differently. I wrote Apple Turnover because so many of my notions kept running into a dead end: I could no longer bring myself to believe Apple would do these things without a change in leadership.

When a company is described as being “in turnaround,” that usually means it needs to be restored to financial health and solvency. Apple in the late 1990s was in turnaround. Apple today is one of the most successful companies in the history of the world, regularly reporting huge profits, so the term may seem inapplicable.

There’s an old adage: never let a good crisis go to waste. When things get bad, people are more open to changes they previously wouldn’t consider. But avoiding a crisis entirely is even better. This is where Apple finds itself today: in need of turnaround-scale changes, but not currently in the kind of (usually financial) crisis that will motivate its leaders to make them.

New leadership is almost always part of a turnaround. In part, that’s because poor financial performance is one of the few remaining sins for which CEOs are reliably held to account. But it’s also because certain kinds of changes need the credibility that only new faces can bring.

So what are those changes? What are the things I think Apple should do, but that its current leadership seems unwilling to budge on? What changes require a level of engagement and understanding that Apple no longer seems to have?

A New Deal for Developers

Apple’s relationship with developers is an essential part of its long-term success. Apple cannot do everything on its own. It needs third-party developers to expand the capabilities of its products and platforms. Developers make Apple’s products more valuable.

Apple needs the things third-party developers produce, but it also needs something else: their trust and enthusiasm. When the iPhone was introduced in 2007—without support for third-party apps—Apple’s developer community was on fire with the desire to create their own iPhone apps. They wanted it so badly that they hacked their way to success even before Apple announced the iPhone SDK in 2008. This passion from developers helped rocket the platform to its current astronomical level of success. The iPhone was a rising tide that lifted all boats—at the start, anyway.

Today, developers are unsatisfied with their relationship with Apple. There are plenty of rational arguments for why they “shouldn’t” be, but as I argued in The Art of the Possible, none of that changes the facts on the ground.

Could Apple’s current leadership change some policies to turn this around? Maybe, but it would be an uphill climb to win back what has been lost. For years, Apple has refused to do what it takes to heal this divide. Even when ordered by the courts to make changes in this area, Apple has worked hard to ensure that its “compliance” with these rulings does as little as possible to make things better for developers. And all the while, Apple has done everything in its power (and some things beyond) to fight the changes.

So, yeah, it would be very hard for that Apple to convince developers that it has turned over a new leaf, even if it wanted to. (And, thus far, it very much does not want to.) New leadership would have a more convincing story and a stronger mandate for change.

When thinking about what those changes might be, it’s tempting to believe it would be as simple as altering the revenue split between developers and Apple. But money is not actually the heart of the matter. Witness how developer sentiment did not appreciably improve when Apple lowered its App Store commission from 30% to 15% in 2020 for businesses earning less than $1 million per year.

Developers like money, but what they need is respect. What they need is to feel like Apple listens to them and understands their experience. What they need is to be able to make their own decisions about their products and businesses.

To understand just how little power the App Store commission rate alone has to heal this relationship, consider how Apple might leave the rate unchanged and still turn developer sentiment around. Maybe something like this…

Start by changing App Review from a Kafkaesque nightmare to a sane, functioning, supportive process in which Apple and developers work together to successfully release software. That means timely, two-way communication with recognizably human entities at Apple. App reviewers should be able to convince developers that they have both read and understood their messages, and they should be empowered to help solve problems.

Next, create a public bug tracker (with an option for developers to keep some information or entire bug reports private to ensure proprietary information is not exposed). Develop Apple’s own software “in the open” as much as possible. Publish average response times and fix times for bugs, and maintain those numbers at levels that satisfy developers.

Finally, remove all restrictions on third-party payment methods and app stores. Provide an even playing field (to the extent possible) for third-party replacements for Apple’s own store and payment systems. Freedom of choice is the best way—perhaps the only way—to ensure that developers are satisfied with Apple’s App Store commission, in-app purchase system, and app review process. Developers who don’t like it can go elsewhere. If Apple wants them back, it will have to compete for their business.

An Apple that does all of this well could maintain its current App Store commission while also satisfying its developers.

In the end, the details don’t matter as much as choosing the correct way to measure success. Apple will know it has succeeded when third-party developers feel like Apple is their partner in success, rather than their adversary or overlord.

A Premium Experience for Premium Prices

One of the best ways to command high prices while maintaining customer satisfaction is to cultivate a reputation for standing behind your products. Apple today is actually pretty good at this. Its hardware is mostly sturdy and reliable, and its support experience is arguably among the best in the industry (even if that is an admittedly low bar).

But there’s one area where Apple falls far short of its ideals: software reliability. Premium brands accrue tremendous customer loyalty when their products work as expected. When it comes to software, achieving this goal requires the relentless pursuit of bugs until the ones that remain are so uncommon that most people never see them.

Though it might not be obvious to people who have never worked in the software industry, this is actually a leadership issue. Striking the correct balance between creating new features and ensuring that existing features work correctly (and gradually improve) requires leadership dedicated to this strategy.

Nearly everything in this industry will push leaders in the opposite direction. New features drive sales. When there’s a hot new technology, companies need to show that they’re able to use it, lest they get left behind. These are all good, important motivators—which is why it’s so incredibly hard for leaders to successfully defend the far less glamorous practices of fixing bugs and enhancing existing features.

But defend they must. Adding features wins games, but bug fixing wins championships.

It’s been 15 years since Apple’s leadership last demonstrated that it’s willing to emphasize software reliability at the cost of new features. Since then, bugs in major features have been allowed to fester, unfixed, for years on end.

The recent Apple Intelligence fiasco has revealed that the company is further away from properly prioritizing software reliability than it has ever been. Apple was seemingly willing to sacrifice everything, including its own reputation, to ensure that it had enough new AI features to announce at WWDC. If we want a different result, it seems like we need different leaders.

Growth the Hard Way

As iPhone sales have plateaued, Apple has turned to services revenue to maintain its growth. Unfortunately, selling more and more services to your existing customers is inherently corrosive to the core philosophy that has led to Apple’s tremendous success. Here’s Steve Jobs describing where former Apple CEO John Sculley went wrong:

“My passion has been to build an enduring company where people were motivated to make great products. The products, not the profits, were the motivation. Sculley flipped these priorities to where the goal was to make money. It’s a subtle difference, but it ends up meaning everything.” ―Steve Jobs

With every red badge in iOS Settings, every pop-up come-on to subscribe to Apple TV+, and every multi-billion-dollar product placement deal, Apple chips away at the customer experience in exchange for income growth.

The pursuit of financial success above all else inevitably leads to ruin. In the past, Tim Cook has demonstrated that he does understand this. But thus far, his dedication to services revenue growth has been unshakable. He either doesn’t agree that this runs counter to Apple’s core values, or he’s willing to undermine those values in exchange for growth.

New leadership at Apple will surely face similar pressure to continue growing. If pursuing services revenue is off the table, what options remain?

It’s conventional wisdom that iPhone sales have leveled off now that Apple has “run out of people.” Nearly every human who can afford a smartphone already has one. But they don’t all have iPhones. Android phones still dominate in worldwide market share.

If Apple wants growth, it should try winning some new customers the old-fashioned way: by making products that more people want to buy. In this case, that means making iPhones that current Android customers want to buy…and can afford.

Historically, going down-market has been anathema to Apple. Apple’s pricing is an important market signal that communicates product quality and desirability. It’s unrealistic to assume that Apple can compete with the lowest of the low-end Android phones. But it’s equally absurd to believe that the current market share line between Android (~70%) and Apple (~30%) is unmovable. Millions of “iPhone-class” (and iPhone-priced) Android phones are sold every year. Apple can and should compete for that business.

Future Days

This list of suggestions is not exhaustive. An inventory of all the things Apple should do would include getting its house in order when it comes to AI, reducing its dependence on China, hitting its 2030 environmental goals, making a decent Mac Pro again, and a million other things, most of which Apple can accomplish as it exists today.

This article is specifically about the things it seems like Apple can’t or won’t do without new leadership. I’ve described three of the most important and impactful, but there’s more. That’s the promise and the danger of regime change. New people have a chance to rise above the sins of the past and make new choices. They can also make new mistakes, and they’ll have their own strengths and weaknesses. There is no such thing as a perfect leader.

For example, if I had to pick one person to successfully transition Apple away from its current level of dependence on China, it would be Tim Cook. But that job will take many more years, and Cook has said he probably won’t be at Apple much past the end of the decade.

Finding a good successor for Tim Cook won’t be easy, no matter when it happens. But it does have to happen, and sooner is better than later.

I hope I’m wrong about all this. I hope Apple’s current leaders take a hard look at some of these longstanding issues and are brave enough to change their minds. Faith lost can be restored, with effort. Either way, as always, I’m pulling for Apple to succeed.

Apple Turnover

Mac users of a certain age may remember Ambrosia Software, maker of iconic shareware hits like Maelstrom and Escape Velocity. For over a decade, the Ambrosia website included this quotation on its homepage:

“Virtue does not come from money, but rather from virtue comes money, and all other things good to man.” ―Socrates

In other words, don’t try to make money. Try to make great things, and the money will surely follow. It’s a strategy that’s simple to explain, but almost impossible for any company to follow.

Folks in the C-suite will try to tell you that these two goals are perfectly aligned—that making great products is part of being a profitable company. But they mean it in the same way that Frosted Flakes is part of a complete breakfast. It’s on the table, sure…along with a glass of milk, a poached egg, toast with jam, and a piece of fruit. It turns out that, as far as big corporations are concerned, one part of this spread is actually kind of optional.

From virtue comes money, and all other good things. This idea rings in my head whenever I think about Apple. It’s the most succinct explanation of what pulled Apple from the brink of bankruptcy in the 1990s to its astronomical success today. Don’t try to make money. Try to make a dent in the universe. Do that, and the money will take care of itself.

Turn, Turn, Turn

Dissatisfaction with Apple among its most ardent fans has, at various times, reached a crescendo that has included public demands for a change in leadership. The precipitating events could be as serious as Apple bowing to pressure from an authoritarian regime, or as trivial as releasing an unsatisfying new version of an application or operating system.

Despite making my living by criticizing Apple, I tend not to get caught up in the controversy of the moment. When Apple ruined its laptop keyboards, I wasn’t calling for Tim Cook’s head. I just wanted them to fix the keyboards. And they did (eventually).

But success hides problems, and even the best company can lose its way. To everything, there is a season.

As far as I’m concerned, the only truly mortal sin for Apple’s leadership is losing sight of the proper relationship between product virtue and financial success—and not just momentarily, but constitutionally, intransigently, for years. Sadly, I believe this has happened.

The preponderance of the evidence is undeniable. Too many times, in too many ways, over too many years, Apple has made decisions that do not make its products better, all in service of control, leverage, protection, profits—all in service of money.

To be clear, I don’t mean things like charging exorbitant prices for RAM and SSD upgrades on Macs or taking too high a percentage of in-app purchases in the App Store. Those are venial sins. It’s the apparently unshakable core beliefs that motivate these and other poor decisions that run counter to the virtuous cycle that led Apple out of the darkness all those years ago.

Apple, as embodied by its leadership’s decisions over the past decade or more, no longer seems primarily motivated by the creation of great products. Time and time again, its policies have made its products worse for customers in exchange for more power, control, and, yes, money for Apple.

The iPhone is a better product when people can buy ebooks within the Kindle app. And yet Apple has fought this feature for the past fourteen years, to the tune of millions of dollars in legal fees, and has only relented due to a recent court order (which they continue to appeal).

In the (Apple-mandated) absence of competition in the realms of app sales, payment processing, customer service, and software business models, Apple’s exclusive offerings in these areas have stagnated for years. What should be motivating Apple to make improvements—the desire to make great products—seems absent. What should not be motivating Apple—the desire for power, control, and profits—seems omnipresent.

And I don’t mean that in a small way; I mean that in a big way. Every new thing we learn about Apple’s internal deliberations surrounding these decisions only lends more weight to the conclusion that Apple has lost its north star. Or, rather, it has replaced it with a new, dark star. And time and again, we’ve learned that these decisions go all the way to the top.

The best leaders can change their minds in response to new information. The best leaders can be persuaded. But we’ve had decades of strife, lawsuits, and regulations, and Apple has stubbornly dug in its heels even further at every turn. It seems clear that there’s only one way to get a different result.

In every healthy entity, whether it’s an organization, an institution, or an organism, the old is replaced by the new: CEOs, sovereigns, or cells. It’s time for new leadership at Apple. The road we’re on now does not lead anywhere good for Apple or its customers. It’s springtime, and I’m choosing to believe in new life. I swear it’s not too late.

For more on this topic, see the follow-up article: Apple Turnaround

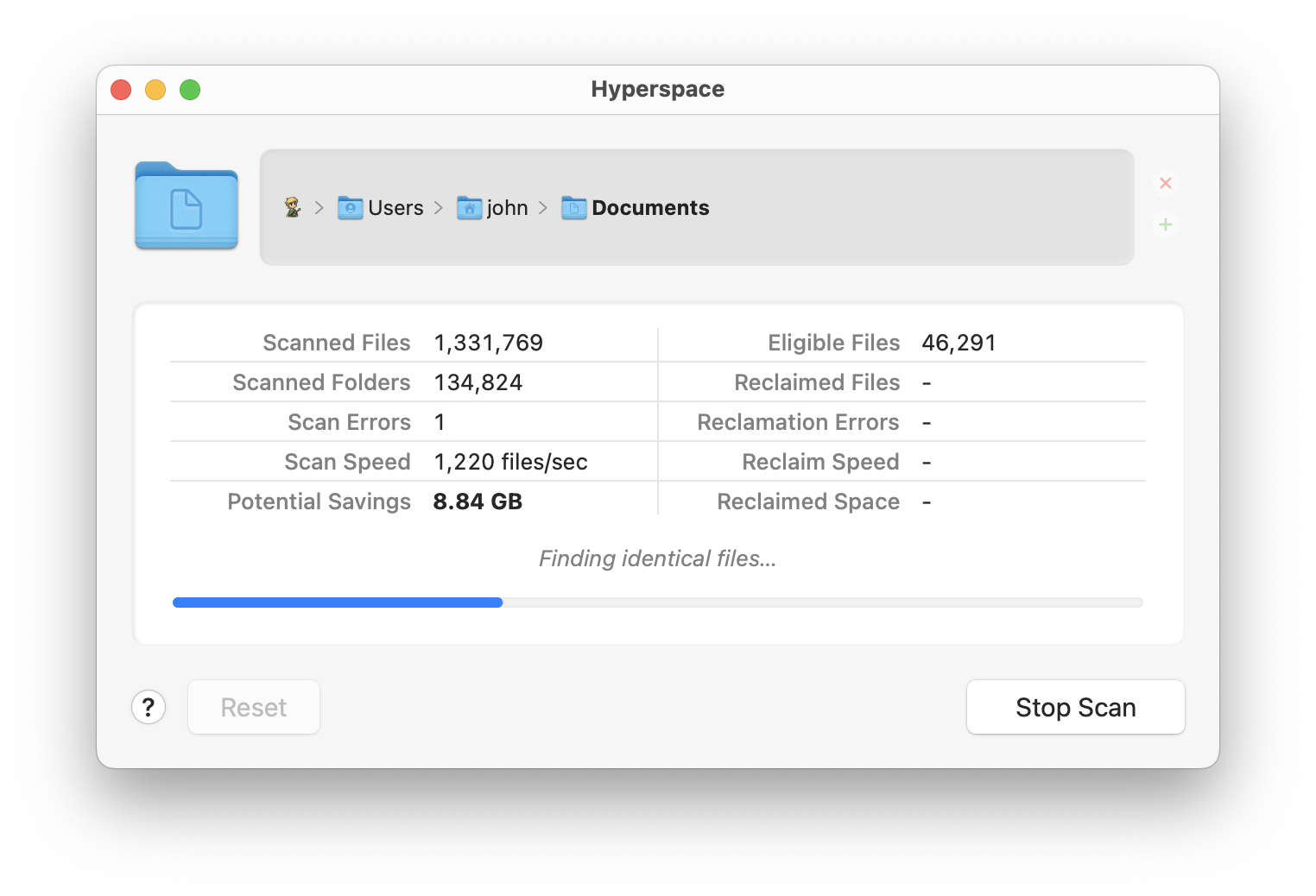

Hyperspace Update

Two months ago, I launched Hyperspace, a Mac app for reclaiming disk space without removing files. The feature set of version 1.0 was intentionally very conservative. As I wrote in my launch post, Hyperspace modifies files that it did not create and does not own. This is an inherently risky proposition.

The first release of Hyperspace mitigated these risks, in part, by entirely avoiding certain files and file system locations. I knew lifting these limitations would be a common request from potential customers. My plan was to launch 1.0 with the safest possible feature set, then slowly expand the app’s capabilities until all these intentional 1.0 limitations were gone.

With the release of Hyperspace 1.3 earlier this week, I have accomplished that goal. Here’s the timeline for overcoming the three major 1.0 feature limitations:

- 1.0: February 24, 2025 - Launch

- 1.1: March 14, 2025 - Packages

- 1.2: April 3, 2025 - Cloud storage

- 1.3: April 28, 2025 - Libraries

Here’s an explanation of those limitations, why they existed, and what it took to overcome them.

Packages

A “package” is a directory that is presented to the user as a file. For example, an .rtfd document (a “Rich Text Document With Attachments”) created by TextEdit is actually a directory that contains an .rtf file plus any attachments (e.g., images included in the document). The Finder displays and handles this .rtfd directory as if it were a single file.

For a package to work, all its contents must be intact. Hyperspace works hard to handle and recover from all sorts of errors, but in the rare case that manual intervention is required, asking the user to fix a problem within a package is undesirable. Since packages appear as single files, most people are not accustomed to cracking them open and poking around in their guts.

This may all seem esoteric, but there are some kinds of packages that are widely used and often contain vast amounts of data. Let’s start with the big one: Apple Photos libraries are packages. So are iMovie libraries, some Logic projects, and so on. These packages are all ideal targets for Hyperspace in terms of potential space savings. But they also often contain some of people’s most precious data.

For the most part, files within packages don’t need to be treated any differently than “normal” files. The delay in lifting this limitation was to allow the app to mature a bit first. Though I had a very large set of beta testers, there’s nothing like real customer usage to find bugs and edge cases. After five 1.0.x releases, I finally felt confident enough in Hyperspace’s basic functionality to allow access to packages.

I did so cautiously, however, by adding settings to enable package access, but leaving them turned off by default. I also provided separate settings for scanning inside packages and reclaiming files within packages. Enabling scanning but not reclamation within packages allows files within packages to be used as “source files”, which are never modified.

Finally, macOS requires special permissions for accessing Photos libraries, so there’s a separate setting for that as well.

Oh, and there’s one more common package type that Hyperspace still ignores: applications (i.e., .app packages). The contents of app packages are subject to Apple’s code signing system and are very sensitive to changes. I still might tackle apps someday, but it hasn’t been a common customer request.

Cloud Storage

Any file under the control of Apple’s “file provider” system is considered to be backed by cloud storage. In the past, iCloud Drive was the only example. Today, third-party services also use Apple’s file provider system. Examples include Microsoft OneDrive, Google Drive, and some versions of Dropbox.

There’s always the potential for competition between Hyperspace and other processes when accessing a given file. But in the case of cloud storage, we know there’s some other process that has its eye on every cloud-backed file. Hyperspace must tread lightly. Also, files backed by cloud storage might not actually be fully downloaded to the local disk. And even if they are, they might not be up-to-date.

Unlike files within packages, files backed by cloud storage are not just like other files. They require special treatment using different APIs. After nailing down “normal” file handling, including files within packages, I was ready to tackle cloud storage.

In the end, there were no major problems. Apple’s APIs for wrangling cloud-backed files mostly seem to work, with only a few oddities. And if Hyperspace can’t get an affirmative assurance from those APIs that a file is a valid candidate for reclamation, it will err on the side of caution and skip the file instead.

Libraries

In the early years of Mac OS X, there were tragicomic tales of users finding a folder named “Library” in their home directory and deciding they didn’t need it or its contents, then moving them to the Trash. Today, macOS hides that folder by default—for good reason. Its contents are essential for the correct functionality of your Mac! The same goes for the “Library” directory at the top level of the boot volume.

Hyperspace avoided Library folders for so long because their contents are so important, and because those contents are updated with surprising frequency. As with packages, it was important for me to have confidence in the basic functionality of Hyperspace before I declared open season on Library folders.

This capability was added last because the other two were more highly requested. As usual, Library access is enabled with a setting, which is off by default. Due to the high potential for contention (running apps are constantly fiddling with their files within the Library folder), this is probably the riskiest of the three major features, which is another reason I saved it for last. I might not have added it at all, if not for the fact that Library folders are a surprisingly rich source for space savings.

The Future

There’s more to come, including user interface improvements and an attempt to overcome some of the limitations of sandboxing, potentially allowing Hyperspace to reclaim space across more than one user account. (That last one is a bit of a “stretch goal”, but I’ve done it before.)

If you want to know more about how Hyperspace works, please read the extensive documentation. If you're interested in beta testing future versions of Hyperspace, email me.

In some ways, Hyperspace version 1.3 is what I originally envisioned when I started the project. But software development is never a straight line. It’s a forest. And like a forest it’s easy to lose your way. Launching with a more limited version 1.0 led to some angry reviews and low ratings in the Mac App Store, but it made the app safer from day one, and ultimately better for every user, now and in the future.

Love, Death & Robots

Love, Death & Robots is an animated anthology series on Netflix. Each episode is a standalone story, though there is the barest of cross-season continuity in the form of one story featuring characters from a past season.

I love animation, but I’m hesitant to recommend Love, Death & Robots to casual viewers for a couple of reasons. First, this show is not for kids. It features a lot of violence, gore, nudity, and sex. That’s not what most people expect from animation.

Second, the quality is uneven. I don’t mean the quality of the animation, which is usually excellent. I mean how well they work as stories. Each episode has only a ten- to fifteen-minute runtime, during which it has to introduce its characters, its (usually sci-fi) setting, and then tell a satisfying story. It’s a challenging format.

Three seasons of Love, Death & Robots have been released since 2019. With season four set to debut in May, I thought I’d take a shot at convincing more people to give this show a chance. This is a rare case where I don’t recommend starting with season 1, episode 1 and viewing in order. The not-so-great episodes will surely drive most people away. Instead, I’m going to tell you where the gems are.

Here’s my list of the very best episodes of Love, Death & Robots in seasons 1–3. They’re standalone stories, so you can watch them in any order, but (back on brand) I do recommend that you watch them in the order listed below.

One last warning: Though not every episode is filled with gore and violence, most of them are—often including sexual violence. If this is not something you want to see, then I still recommend watching the handful of episodes that avoid these things. Remember, each episode is a standalone story, so watching even just one is fine.

-

Sonnie’s Edge (Season 1, Episode 1) - This is a perfect introduction to the series. It’s grim, violent, gory, beautifully animated, but with some unexpected emotional resonance.

-

Three Robots (Season 1, Episode 2) - The characters introduced in this story have become the unofficial mascots of the series. You’ll be seeing them again. The episode is lighthearted, cute, and undercut by a decidedly grim setting.

-

Good Hunting (Season 1, Episode 8) - Yes, traditional 2D animation is still a thing! But don’t expect something Disney-like. This story combines fantasy, myth, sci-fi, sex, love, death, and…well, cyborgs, at least.

-

Lucky 13 (Season 1, Episode 13) - If you like sci-fi action as seen in movies like Aliens and Edge of Tomorrow, this is the episode for you. As expected for this series, there’s a bit of a cerebral and emotional accent added to the stock sci-fi action.

-

Zima Blue (Season 1, Episode 14) - This is my favorite episode of the series, but it’s a weird one. I’m sure it doesn’t work at all for some people, but it got me. There’s no violence, sex, or gore—just a single, simple idea artfully realized.

-

Snow in the Desert (Season 2, Episode 4) - There’s a full movie’s worth of story crammed into this 18-minute episode, including some nice world-building and a lot of familiar themes and story beats. There’s nothing unexpected, but the level of execution is very high.

-

Three Robots: Exit Strategies (Season 3, Episode 1) - Our lovable robot friends are at it again, with an extra dose of black humor.

-

Bad Travelling (Season 3, Episode 2) - Lovecraftian horror on the high seas. It’s extremely dark and extremely gross.

-

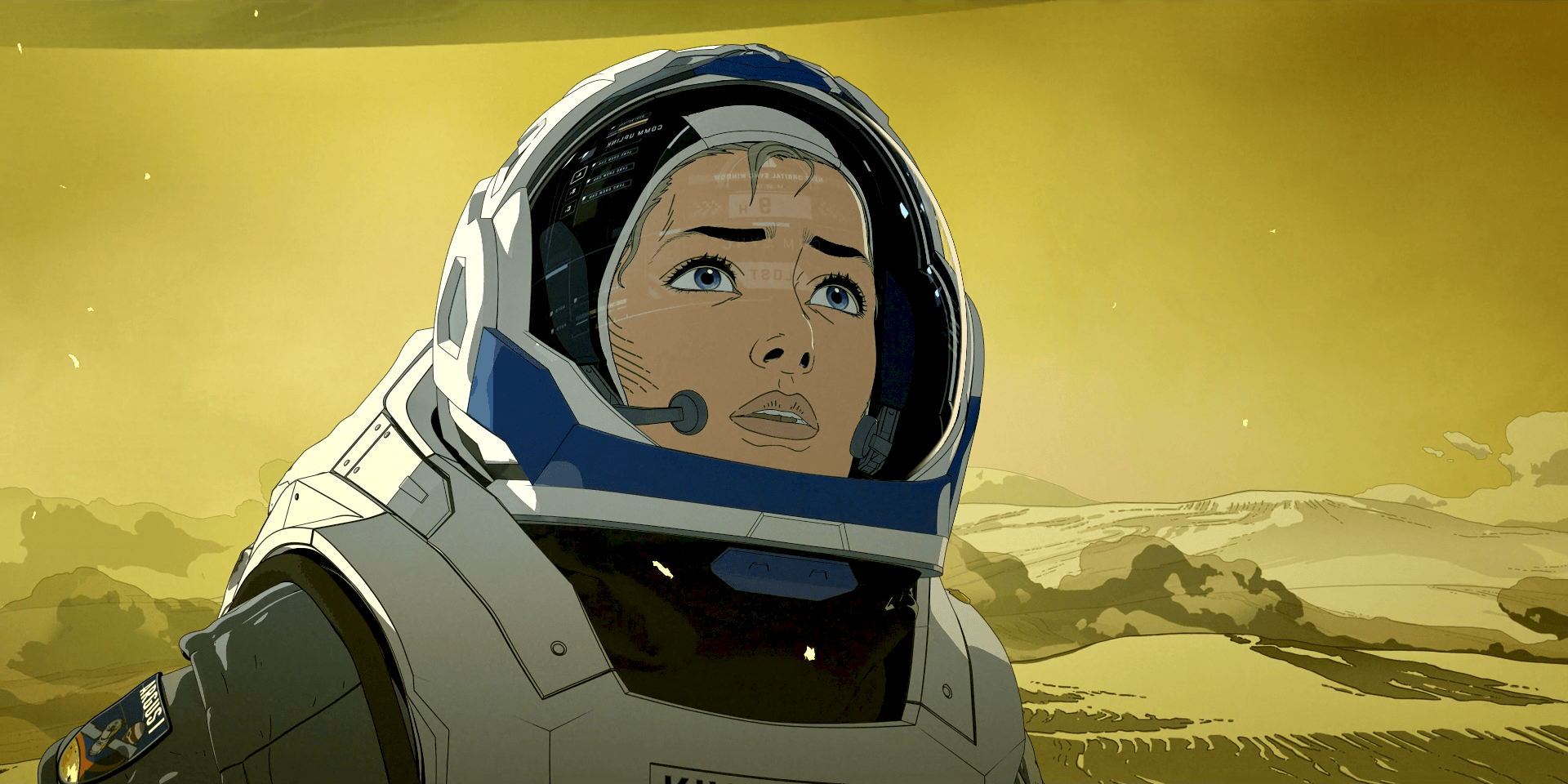

The Very Pulse of the Machine (Season 3, Episode 3) - I guess I like the sappy, weird ones the best, because this is my second-favorite episode. It combines the kind of sci-fi ideas usually only encountered in novels with an emotional core. The animation is a beautiful blend of 3D modeling and cel shading. (As seen in Frame Game #75)

-

Swarm (Season 3, Episode 6) - I’ll see your Aliens-style sci-fi and raise you one pile of entomophobia and body horror. Upsetting and creepy.

-

In Vaulted Halls Entombed (Season 3, Episode 8) - “Space marines” meets Cthulhu. It goes about as well as you’d expect for our heroes.

-

Jibaro (Season 3, Episode 9) - The animation style in this episode is bonkers. I have never seen anything like it. The story, such as it is, is slight. This episode makes the list entirely based on its visuals, which are upsetting and baffling and amazing in equal measure. I’m not sure I even “like” this episode, but man, is it something.

If you’ve read all this and still can’t tell which are the “safest” episodes for those who want to avoid gore, sex, and violence, I’d recommend Three Robots (S1E2), Zima Blue (S1E14), Three Robots: Exit Strategies (S3E1), and The Very Pulse of the Machine (S3E3). But remember, none of these episodes are really suitable for children.

If you watch and enjoy any of these, then check out the rest of the episodes in the series. You may find some that you like more than any of my favorites.

Also, if you see these episodes in a different order in your Netflix client, the explanation is that Netflix rearranges episodes based on your viewing habits and history. Each person may see a different episode order within Netflix. Since viewing order doesn’t really matter in an anthology series, this doesn’t change much, but it is unexpected and, I think, ill-advised. Regardless, the links above should take you directly to each episode.

I’m so excited that a series like this even exists. It reminds me of Liquid Television from my teen years: a secret cache of odd, often willfully transgressive animation hiding in plain sight on a mainstream media platform. They’re not all winners, but I treasure the ones that succeed on their own terms.

Hyperspace

My interest in file systems started when I discovered how type and creator codes1 and resource forks contributed to the fantastic user interface on my original Macintosh in 1984. In the late 1990s, when it looked like Apple might buy Be Inc. to solve its operating system problems, the Be File System was the part I was most excited about. When Apple bought NeXT instead and (eventually) created Mac OS X, I was extremely enthusiastic about the possibility of ZFS becoming the new file system for the Mac. But that didn’t happen either.

Finally, at WWDC 2017, Apple announced Apple File System (APFS) for macOS (after secretly test-converting everyone’s iPhones to APFS and then reverting them back to HFS+ as part of an earlier iOS 10.x update in one of the most audacious technological gambits in history).

APFS wasn’t ZFS, but it was still a huge leap over HFS+. Two of its most important features are point-in-time snapshots and copy-on-write clones. Snapshots allow for more reliable and efficient Time Machine backups. Copy-on-write clones are based on the same underlying architectural features that enable snapshots: a flexible arrangement between directory entries and their corresponding file contents.

Today, most Mac users don’t even notice that using the “Duplicate” command in the Finder to make a copy of a file doesn’t actually copy the file’s contents. Instead, it makes a “clone” file that shares its data with the original file. That’s why duplicating a file in the Finder is nearly instant, no matter how large the file is.

Despite knowing about clone files since the APFS introduction nearly eight years ago, I didn’t give them much thought beyond the tiny thrill of knowing that I wasn’t eating any more disk space when I duplicated a large file in the Finder. But late last year, as my Mac’s disk slowly filled, I started to muse about how I might be able to get some disk space back.

If I could find files that had the same content but were not clones of each other, I could convert them into clones that all shared a single instance of the data on disk. I took an afternoon to whip up a Perl script (that called out to a command-line tool written in C and another written in Swift) to run against my disk to see how much space I might be able to save by doing this. It turned out to be a lot: dozens of gigabytes.

At this point, there was no turning back. I had to make this into an app. There are plenty of Mac apps that will save disk space by finding duplicate files and then deleting the duplicates. Using APFS clones, my app could reclaim disk space without removing any files! As a digital pack rat, this appealed to me immensely.

By the end of that week, I’d written a barebones Mac app to do the same thing my Perl script was doing. In the months that followed, I polished and tested the app, and christened it Hyperspace. I’m happy to announce that Hyperspace is now available in the Mac App Store.

Hyperspace is a free download, and it’s free to scan to see how much space you might save. To actually reclaim any of that space, you will have to pay for the app.

Like all my apps, Hyperspace is a bit difficult to explain. I’ve attempted to do so, at length, in the Hyperspace documentation. I hope it makes enough sense to enough people that it will be a useful addition to the Mac ecosystem.

For my fellow developers who might be curious, this is my second Mac app that uses SwiftUI and my first that uses the SwiftUI life cycle. It’s also my second app to use Swift 6 and my first to do so since very early in its development. I found it much easier to use Swift 6 from (nearly) the start than to convert an existing, released app to Swift 6. Even so, there are still many rough edges to Swift 6, and I look forward to things being smoothed out a bit in the coming years.

In a recent episode of ATP, I described the then-unnamed Hyperspace as “An Incredibly Dangerous App.” Like the process of converting from HFS+ to APFS, Hyperspace modifies files that it did not create and does not own. It is, by far, the riskiest app I’ve created. (Reclaiming disk space ain’t like dusting crops…) But I also think it might be the most useful to the largest number of people. I hope you like it.

Please note that type and creator codes are not stored in the resource fork. ↩