Hypercritical

We Can Remember It for You Wholesale

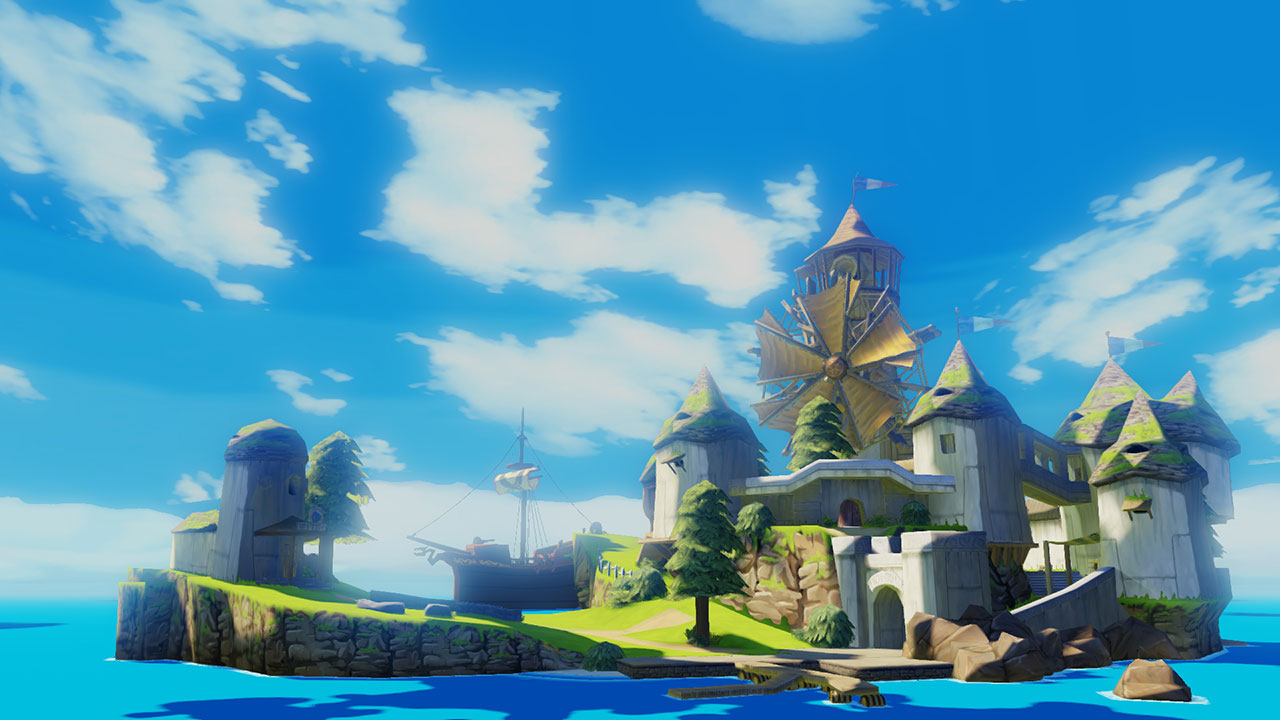

The highlight of Nintendo’s video presentation this week was the announcement of a Wii U remake of The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, a GameCube game originally released in the US a decade ago. As a dedicated Zelda fan, my reaction was predictably enthusiastic.

Elsewhere on the net, fretting about the content and appearance of the game started immediately. It made me think about why I’m such a fan of video game remakes while my default position on movie remakes is to turn up my nose at them. How can I hate the Star Wars special editions but love the HD remakes of Ico and Shadow of the Colossus? I think both sentiments have the same underlying motivation: I don’t want to lose the things I love.

In the case of Star Wars, I’m frustrated not so much by the existence of alternate versions of the movies, but by the disappearance of the original theatrical releases. I discussed this at length in episode 45 of the Hypercritical podcast (the topic starts at 35:57), but here’s a summary: Artists are often not the best stewards of their own work. Once an artistic creation reaches a certain level of cultural significance, it belongs to society at large more than it belongs to the creators—philosophically, if not legally. Cultural touchstones belong to all of us, and they deserve to be treasured and preserved, regardless of the creator’s wishes.

Video games are an odd art form in many ways, one of which is that they’re extremely dependent on their delivery platform. More established kinds of art like paintings, books, video, and audio recordings have all proven resilient to changes in technology. The novels of Charles Dickens did not disappear as book technology evolved. Most filmmakers have been vigilant about preserving and (eventually) digitizing movies that were shot on film. (Again, Star Wars stands out as a sad exception.) All these art forms have a clear path to move forward in time; they’ll always be with us.

Video games are a different story. Historically, video game platform owners have been unwilling or unable to preserve the works of art originally delivered on their platforms. When the Wii, PS3, and Xbox 360 all launched with some ability to play games made for the consoles they replaced, I was optimistic about the future. But the PS3’s ability to play PS2 games rapidly diminished, first losing dedicated hardware support and then disappearing completely. Similarly, the latest iteration of the Wii can’t play GameCube games. Hoarding and preserving console launch hardware started to make a lot more sense.

Today, Nintendo sells its own emulated versions of many of its classic games. Presumably this will extend to Wii U games when that hardware is eventually phased out. But I have little faith in Nintendo’s motivation to preserve its past beyond its function as an income source. And let’s not forget all the important video game makers that have gone out of business—or been acquired and re-acquired so many times that they might as well have.

Again, as in the case of Star Wars, it has fallen to the fans to preserve classic games, sometimes by preserving the original hardware, but most often through emulation. This doesn’t just apply to video games that are 30 years old. Games are becoming inaccessible so rapidly that even platforms created just a handful of years ago already have active emulation projects.

That’s the fear that HD remakes tap into. Though there are many things that can go wrong when an older video game is ported and “improved” for release on a newer hardware platform, the risks are vastly outweighed in my mind by the playable-lifespan extension that a remake bestows on a beloved game.

Right now, I can play Wind Waker on my GameCube and my Wii. Newer Wiis (and the Wii U) don’t play GameCube games. Both the GameCube and the Wii send their video signal over a component cable, at best. I suspect TVs will stop shipping with component video inputs in a few years, which will leave me at the mercy of video converter boxes. Eventually, no matter how well I care for them, my 12-year-old GameCube and my 7-year-old Wii will break. (The optical drives will probably go first.) But when that happens, my Wii U, with its HDMI connection and 2012 manufacture date, will probably still be working. Time extended!

Alas, things get even more complicated when you consider not just the software but also the controller hardware and the details of the display device. I’ve still got my N64 in the attic, but my son experienced Ocarina of Time by playing the GameCube port on the Wii connected to a plasma HDTV. Was it the same as playing the original using an N64 controller and an old CRT television? Well, not quite. This problem only gets worse as the hardware gets more novel.

In the end, I’m content to at least preserve the software in some playable form, even if the controller and display are slightly different. Just doing this is turning out to be enough of a fight. I hope my purchase of the Wii U remake of Wind Waker will help convince Nintendo and other game makers that older titles are valued by gamers long past the death of their original platforms.

I’m also a little afraid that remakes like this will delay or prevent the original version of the game from appearing in an officially sanctioned emulated form. But for now, I’ll take what I can get. I’m glad my son has already played the original GameCube version of Wind Waker—twice. I’m also excited to replay Wind Waker with him on the Wii U in HD. It won’t be exactly the same as it was, but I think it’ll still be great. Most importantly, I hope he can share both of these experiences with his children someday.